Political Trajectory: Which Way for Burundi?

|

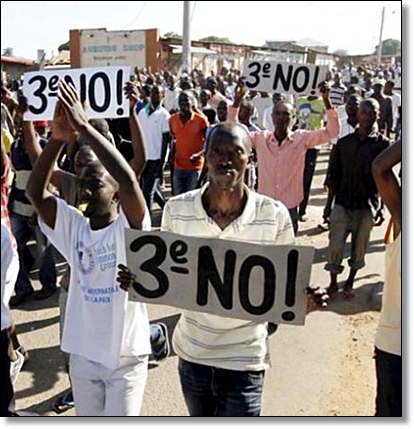

| Burundians stage a demo |

Recapitulation of last year’s events

In the aftermath of the decade-long bloody civil war and following prolonged political negotiations from Kigobe and Kajaga (Burundi) through San Egidio (Italy) and Sun City (South Africa) to Mwanza and Arusha (Tanzania), Burundians adopted a Constitution which requires a two thirds majority for the passing of any bill tabled in the Parliament. This was ingeniously adopted to avoid the excess of power by simple majority rule and to bring the ruling party to exercise its power in concert with the Opposition.

By end of year 2014, contrary to what members from the ruling party CNDD-FDD considered with regard to the amendment of some provisions in the current Constitution to allow for the candidature the incumbent President in the forthcoming general elections, members of the political opposition as well as civil society underscored that if anything in the Constitution were to change, this should be done by not simply relegating the matter to the National Assembly (where the ruling party holds majority of seats) but rather by engaging with all stakeholders in the public life, including members of the political opposition and civil society.

Then, Burundi’s former President, Senator Domitien Ndayizeye, murmured that any proposal of amendment of Article 299 of the present-day Burundian Constitution—in a bid to secure a third presidential term for incumbent President Pierre Nkurunziza—would have far-reaching repercussions on efforts for the rebuilding of the political as well as socio-economic tissues of a society recovering from a gloomy past. This, Senator Ndayizeye further stated, could negatively affect the yet fragile social cohesion and so negatively impact on national security, to the extent of spilling over neighbouring countries.

As the year 2014 drew to its close, Burundian political party leaders, under the auspices of the First Vice President of the Republic, Bernard Busokoza, gathered at the Royal Palace hotel to proceed with a first evaluation of the implementation of the roadmap for the 2015 elections as well as iron out challenges to its full realization. This roadmap was adopted by consensus at a workshop on the electoral process in Burundi, organised by the Government of Burundi in concert with the Burundi United Nations Bureau (BNUB) from the 11th to the 13th day of March 2013 in Bujumbura. It was hoped that this gathering would allow Burundi’s key political actors to take stock of the implementation of the roadmap thus far as well as identify challenges and opportunities to strengthen the dialogue and democratic culture in Burundi, and so contribute to the creation of a conducive environment for free, fair, inclusive and peaceful elections in 2015. The said roadmap contained general principles and recommendations around four theme, namely; the legal framework for the elections; an enabling environment; electoral management and conduct; and the monitoring mechanism.

History seems to be repeating itself in Burundi after a decade of fragile, hard-won social peace following the signing of the 2000 Arusha Accord. Is the Burundian political elite designing a scenario akin to that of 1993 through such (in)famous roadmap to the 2015 general elections? The unfolding political bickering in the country seems to work against the avoidance of violence in the upcoming 2015 elections, if at all the latter would ever take place. For now, things remain convoluted.

Beyond the incumbency of President Nkurunziza

For a country previously devastated by political violence at a large scale, reducing all political stakes to electioneering by arguing for the right of the candidature of the incumbent president may simply be akin to granting a pain-killer to a patient in urgent need of surgery just as arguing for the utter exclusion of the candidature of the incumbent president at the expense of ‘new comers’ in the search for presidency may be synonymous with placing temporary bandages to a fractured limb. Systemic reforms of the state previously embroiled by political violence seems to be the commensurate dose in curing Burundi’s political ills in a much more rewarding manner.

In the context of post-transition Burundi, the questions of redistribution of land and that of full reintegration of previously exiled populations—whether civilian or armed—have come to the fore of the post-violence debate in the country. More vital, land is access to livelihoods; it allows for the bringing together of family structures that represents a vital coping mechanism in a context of extreme poverty; it symbolises connection with the past, with history, a reaffirmation of identity; and its equitable distribution represents hope for sustainable peace. What is even more critically important to reckon with is the fact that in such a small country with a big population whose livelihoods emanate from farming and livestock, land is in chronically short supply. Therefore, daunting as it may be, addressing current demands on land with the return of approximately half a million people in a way that is simultaneously equitable and feasible is critical to the long-term stability of Burundi.

In the final analysis, whereas the signing of the Arusha Accords as a pact for political justice does still represent a necessary and respectable step in Burundi’s nation-building process, the aspirations found in these Accords would never yield any positive results in the Burundian society unless they faithfully resonate with the deep-seated wishes for capabilities and functionings of local populations, most notably those from the new younger generation. On the one hand, a long events-filled history of conflict, ethnic politicisation and polarisation, authoritarian rule, a decade of civil war, and growing impoverishment will continue to be appended to the reflection of the Burundian reality.

On the other hand, power-sharing arrangements, democratic elections, peace agreements, demobilisation, and an infusion of development aid constitute another reflection of the Burundian reality. What lies in between, Peter Uvin in his latest book on Burundi’s contemporary political history (2009) rightly argues, is a generation of young people raised during times of mass violence (massacres, forced displacements or a brutal civil war) with years of education lost, hearts traumatized, and possessions lost. Some have fought, some have fled, some have stayed, but all have faced dramatically limited opportunities. Yet, these young adults who came of age during the war now represent the future of Burundi. The availability of jobs in a context of severe economic scarcity remains a crucial challenge that any ruling government will have to face—now and the coming future.

Allegorically, to conclude, if some people suffer from inherited diseases, Burundi too suffers from its inherited history. But if molecular biology has come to provide some sparks of hopes for the cure of inherited diseases, only social and economic justice may be the most promising cure for past political violence.

By David-Ngendo Tshimba

MISR PhD Fellow (DNTshimba@gmail.com)