Key Action Points to Industrialize Africa

|

At this point, and within the context of these shared African socio-economic objectives, I would like to draw attention to an important reality – the reality that Nigeria has an obligation it cannot escape, the obligation to play an historic role in terms of helping to lead our Continent to realise its dream, the dream of achieving its renaissance.

When we speak of an African renaissance we mean the birth of an Africa that would have overcome a centuries-long negative legacy we have inherited from the extended period covering the years of the violent export of Africans as slaves, the years of colonialism and neo-colonialism. One tragic consequence of this legacy is the reality we live with everyday – the reality of millions of Africans living in poverty and in conditions of under development. Accordingly, as a strategic objective in terms of achieving Africa’s renaissance, we have the urgent task to confront and defeat this painful reality, thus to eradicate this poverty and under development.

Of course all of us know that there are other important and urgent challenges we face as a Continent. Let me mention two of these. One of these is the need to rid ourselves of the pernicious incidence of violent conflict in and between our countries contrary to the deep-seated wishes of the billion Africans for peace and stability throughout our Continent. The other is the task to confront the continuing reality of the relative marginalisation of Africa in terms of the determination of global affairs, which includes the fact that there are others in the world who still have the arrogance to arrogate to themselves the right to determine our future.

It is important to understand that the economic situation I have mentioned of poverty and underdevelopment on our Continent has a direct relationship with both the two issues I have mentioned – the conflicts in some of our countries and the relative global marginalisation of Africa. Integral to the conflicts in some of our countries is the economic imbalance within these countries resulting in sections of the population feeling marginalised and disempowered, with no choice but to resort to arms to assert their rights, especially inclusion within the national process of equitable wealth sharing. Similarly, it is obvious that a developed Africa, liberated from the scourge of pervasive poverty, would be in a much better and stronger position to stand up for its inalienable right to determine its destiny.

Much has been written and said about the high and sustained rates of economic growth which our Continent has achieved over recent years. It is in this context that the notion of “Africa rising” has gained great currency. However the point has also been made correctly that we realised this important achievement due, in good measure, to a commodity boom – the relatively high prices and strong demand for the raw materials we produce and export.

However, in the context of the vision of an African renaissance, it is clear that the economic successes we achieved, based on the export of raw materials, underlined an unacceptable reality. That reality is that in large measure and so many years after independence, we continue to maintain the system of economic relations with the rest of the world which was developed during the period of colonialism. This continues to make us producers and exporters of raw materials and importers of manufactured goods. This has to change.

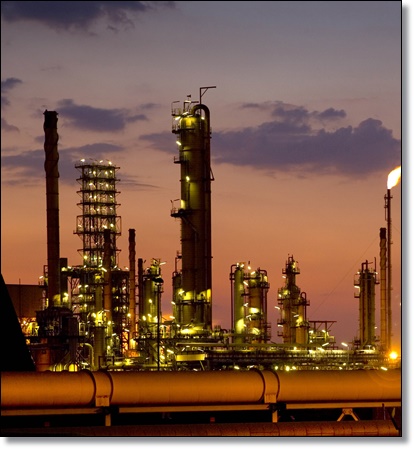

In any case I would like to believe that all of us throughout the Continent have learnt the necessary lesson from what has happened more recently – the drop in the prices and demand for raw materials, including oil and gas. There is now universal agreement throughout Africa that we have an urgent and pressing task to diversify our economies, to industrialise, focusing on manufacturing.

In this regard, I have no doubt whatsoever that all Africa agreed without reservation with our leader, Dr Frank Jacobs, when, during H.E. President Muhammadu Buhari’s visit to Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN) in August this year, he said: “Without doubt, the importance of a robust industrial sector, particularly manufacturing, cannot be over-emphasised. This is because, all over the world, the industrial sector is known to create the highest number of employment opportunities, and by extension, it is the most effective vehicle for poverty reduction and inclusive economy.”

In this regard it was important that even before he was elected President of the Federal Republic, when he accepted his nomination as the Presidential candidate of the APC, General Buhari said: “We shall institute just policies that afford people the dignity of work and pay them a living wage for their sweat and toil. We intend to do this by instituting a national industrial policy, coupled with a national employment directive, that together shall revive and expand our manufacturing sector, creating jobs for our urban population and decreasing our reliance on expensive foreign imports.”

It is indeed very inspiring that since then, President Buhari has not wavered in this commitment, sustaining the determination indicated in the Nigeria Industrial Revolution Plan which had been adopted by the Goodluck Jonathan administration which, among others says: “As part of economic transformation across the continent, African nations should produce more of what they consume and add value to local commodities. This however is only possible through the development of a competitive real sector. A new paradigm is required on the African continent, to change the old policies of exporting raw materials and jobs, without building up capacity in areas of comparative advantage, driven by raw materials, markets, cheap labour, and other strengths…The NIRP’s underlying philosophy is to build Nigeria’s competitive advantage, to broaden the scope of industry, and to accelerate expansion of the manufacturing sector.”

We are fortunate that these observations reflect exactly the positions which have been approved and are being pursued by our Continental organisation, the African Union and its organs. In other words, what Nigeria seeks, to industrialise focusing on manufacturing, is what the whole of Africa is determined to achieve. It is also important to note that the Sustainable Development Goals which were adopted by the UN General Assembly a fortnight ago also include Goal 9 which commits the nations of the world to “Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation.”

Among the targets it sets are:

“(To) promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and, by 2030, significantly raise industry’s share of employment and gross domestic product, in line with national circumstances, and double its share in least developed countries; and,

“Increase the access of small-scale industrial and other enterprises, in particular in developing countries, to financial services, including affordable credit, and their integration into value chains and markets.”

Last July, even before the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, the Action Plan of the International Conference on Financing for Development stated: “We stress the critical importance of industrial development for developing countries, as a critical source of economic growth, economic diversification and value addition. We will invest in promoting inclusive and sustainable industrial development to effectively address major challenges such as growth and jobs, resources and energy efficiency, pollution and climate change, knowledge-sharing, innovation and social inclusion.”

We must therefore hope that practical steps are indeed taken by the entire international community to ensure that the Outcomes and Targets set at the Financing for Development Conference and in the Sustainable Development Goals are realised, and are not allowed to remain only unrealised wishes and targets on paper.

The question therefore remains to be answered – given that our nations, our Continent and the international community are today at one about the objective of industrialisation, focusing on manufacturing, what is to be done?

It is clear that first of all, as Nigeria did, each of our countries should adopt what was called in this country an Industrial Revolution Plan. In this context I am certain that all of us would agree with UNIDO, the UN Industrial Development Organisation, when it says that such a Plan should ‘identify industrial and market opportunities, analyse sectors and segments of high growth potential value-chains and determine where to focus intervention to increase impact according to the governmental priorities and in line with the country’s developmental needs.’

With regard to the Industrial Plan, the second point we must make is that it is important that Government, the private sector and organised labour should engage one another to elaborate such a Plan. In this regard, we must also take into account the views of organised labour as reflected, among others. For instance during May Day two years ago, Idowu Adelakun of the Lagos State Council of the NLC said: “Of great concern to us (workers) are issues of corruption, insecurity and unemployment that successive governments seemed to pay lip service to over the decades. How realistic is the government‘s programme of Vision 2020 without a functional manufacturing sector? My colleagues and I believe that a country that doesn’t have a manufacturing base is asking for doom in this age where countries across the world have embraced the concept of industrial development.”

With regard to the matter of constant consultation with the social partners, President Buhari made an important commitment when, in February this year, he spoke to the Organised Private Sector referring to what the Lagos State government had done to meet with the private sector every six months, to listen to its problems and provide solutions within the following six months, and said: “Government cannot know in detail business developments as they occur because it is too immersed in various aspects of Government… (Therefore) A periodic and regular series of meetings is something I will encourage if you elect me as your next President so that our Government can hear from you at firsthand what we should or should not do to advance business interests…”

The third matter we would like to mention is the absolute need for the government to establish the complex of institutions necessary to ensure the success of the Industrial Plan, which institutions would themselves work closely and continuously with the companies to help them succeed as business ventures. These are what the UN ECA and AU in their 2014 Economic Report on Africa called Industrial Policy Organisations, IPOs. These may include ‘industrial banks; state capacity-building organisations dealing with engineering, marketing and finance; industrial policy coordination units; export processing authorities; small and medium-size enterprise support units; units promoting inward foreign direct investment; bodies looking at food production and import policies; units dealing with union and other labour policies; and infrastructure planning units.’

As the Report says: “IPOs should be focused on formulating goals, developing and then implementing strategies, monitoring processes and evaluating outcomes against the goals…”, and so on.

As my fourth point, I would like to say that, by definition, young and developing corporations have great need to access affordable credit to be able to finance their operations. Clearly where the normal financial institutions are unable to respond to this need, government would have to intervene to address this requirement, hence my mention earlier of public sector industrial banks. In this context you know that a Panel I had the privilege to chair produced a Report on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, which the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government adopted in January this year. Happily, the positions and Recommendations contained in that Report are now also contained in the Action Plan adopted by the July International Conference on Financing for Development, thus imposing various obligations on the international community as a whole to fight these illicit financial outflows.

As our Panel’s Report indicated, our Continent loses at least $50 billion a year through trade mispricing alone. All of us know that retention of at least part of these resources on our Continent would make an important and positive contribution to our development efforts, including industrialisation. As we indicated regarding the need for national cooperation in developing the Industrial Revolution Plan, so do we need similar cooperation to defeat the scourge of illicit financial outflows.

Needless to say, and this is my fifth point, the successful implementation of the Industrial Revolution Plan requires what we earlier mentioned as identifying market opportunities. In this context I would like to mention only two matters. These are the issue of regional integration and access to the global markets. Later I will make a short reference to the matter of the domestic market.

I believe that there is no need here to speak at length about the importance of the issue of regional integration and its role in creating the larger markets our economies need in the context of properly functioning Free Trade Areas. Our Continent has been acting on this matter for a number of decades already and, as all of us know, set up, some time ago, such Regional Economic Communities as ECOWAS, SADC, COMESA and others.

The task confronting us in this context is to do the additional and detailed work to ensure that we are in practice achieving the integration we aim to achieve. This includes ensuring that where this has not been done already, we have the road and other infrastructure and the integrated services such as customs and immigration, to facilitate the movement of people, goods and services among the countries in the region.

Of course we have also seen other positive developments in this area such as the launch of the COMESA, EAC and SADC Free Trade Area. Of additional importance with regard to this matter is the fact that the AU treats the RECs as vital building blocks with regard to the advance towards African unity.

Then there is the important matter of the access of African manufactures to the international markets. In this regard the only issue I would like to raise is the matter of the Economic Partnership Agreements with the EU, a matter which is of great concern throughout Africa.

As I understand it, all our regions which were involved in the negotiations with the EU on the EPAs have now signed these Agreements. Nevertheless the question remains – have the African concerns relating to the impact of these EPAs on our industrialisation processes been addressed? My own response to that question is – no!

As you will remember, an ACP Summit Meeting was held in Libreville, Gabon in 1997. That meeting adopted The Libreville Declaration which among other things said: “We draw attention to the inequities of the international economic order and to the continued absence of a level playing field, and hence, the need for special and differential treatment for developing countries in the application of rules and regulations governing international economic transactions.”

To respond to all this the Declaration said the ACP group “attaches importance to the accelerated transformation of our economies and to the critical role of industrialisation in the economic development of our countries” and in the context of the still to be negotiated Cotonou Agreement, called on the EU to continue to “maintain non-reciprocal trade preferences and market access in a successor agreement, and maintain the preferential commodity protocols and arrangements.”

However, I, like many others, was present in the hall in Libreville where this Declaration was adopted, when the then EU Commissioner for Development, João de Deus Pinheiro, told the ACP Summit Meeting that, if I recall his words correctly, ‘the post-colonial period is over’! Indeed he had said exactly this – “The post-colonial days are over.” – when the European Commission adopted its guidelines in October 1997 for the negotiation of the Cotonou Agreement.

EU Commissioner Pinheiro said this because the EU had already developed the view that the preferential treatment which the ACP countries enjoyed under the Lomé Agreement should be replaced by an ACP-EU Free Trade Agreement which would be phased in over a period of ten years.

At a meeting in London in June 1998, Commissioner Pinheiro further explained the EU positions in these words: “The EU must be clear and make an unambiguous offer to the ACP. We think that FTAs are the best option, primarily because they offer more than just market access…FTAs are also the best and simplest way to reconcile the need to ensure WTO compatibility and the EU's political will to maintain current Lomé market access…”

In direct and simple language, what Commissioner Pinheiro meant was that the EU was determined that in the post post-colonial period, as he called it, and after a short transition, the ACP should enter into a system of reciprocal economic relations with the EU. This is what the Economic Partnership Agreements mean.

I am certain that all of us will recall what Sir Ronald Sanders said in Abuja at the end of July when he spoke at the Conference organised to discuss the Economic Partnership Agreements – the EPAs. Echoing The Libreville Declaration adopted eighteen years ago, he said: “‘Reciprocity’ as a principle, has a ring of fairness about it; but that is as between equals. Between factors of unequal strength and capacity, ‘reciprocity’ is more than unfair; it is unjust. If you put a heavyweight and a featherweight in a boxing ring have you staged an equal contest? Is the short-sightedness of this demand for reciprocity, not obvious?”

In this context I am certain that everybody here will recall President Jacobs’ recent comments: “EPA will confine the Nigerian economy to a mere market expansion of the European Union since we cannot operate with Europe on all grounds. It is on these grounds that we believe that Nigeria does not need EPA now until it has been adequately industrialised and is able to trade industrial goods competitively.”

Supporting this position, CONCORD, a European confederation of development NGOs quoted Dieter Frisch, the 1982 to 1993 Director-General for Development of the European Commission, as having said in 2008: “Historically speaking, no case is known of a country in an embryonic stage of its economic development, which has developed itself through opening up to international competition. Development is always initiated…with some protection that could only diminish once and to the extent to which the economy was strong enough to face foreign competition.”

Writing in 2013, Stephen McDonald, Stephen Lande and Dennis Matanda for the US Wilson Center & Manchester Trade said: “The Europeans dangle immediate benefits to a country that is, probably, in need. Despondent, the country, short-sightedly, signs the EPA, allowing Europe to achieve its single-minded objective of leaving a weaker, more disadvantaged and more exploited continent in its wake. Something of this sort started at a Berlin Conference in the 19th Century. But today, Brussels must not set Africa back in time.”

The conclusion from all this is very clear. It is that Africa, together with rest of the ACP, has a difficult struggle ahead – the struggle to ensure that the global economy is restructured in a manner which fully recognises and seeks to correct what The Libreville Declaration identified as “inequities of the international economic order and…the continued absence of a level playing field.”

The solemn commitments made in the Action Plan of the Conference on Financing for Development and in the Sustainable Development Goals agreed at the UN 2015 Sustainable Development Summit reaffirm that “no one will be left behind.” This is the Global Agenda which all humanity should respect and implement, with no exceptions.

The industrialisation we and all Africa are determined to achieve requires that we have access to electricity, transport routes, modern communication technology, skills to give us the required competitive edge, and so on, and therefore the necessary infrastructure to achieve these outcomes. In this regard I would like to recall what H.E. President Buhari said in his Inauguration speech on May 29, that: “No single cause can be identified to explain Nigerian’s poor economic performance over the years than the power situation. It is a national shame that an economy of 180 million generates only 4,000MW, and distributes even less. Continuous tinkering with the structures of power supply and distribution…have only brought darkness, frustration, misery, and resignation among Nigerians. We will not allow this to go on.”

This is a commitment which all our countries should make and honour, and include the other infrastructure we need to develop even our domestic markets, to say nothing about the important matters of the reduction of the cost of doing business and achieving international competitiveness. Our governments bear a particular responsibility in this regard.

Obviously, given its size, Nigeria constitutes a large and important domestic market. The development of the necessary infrastructure is critical to ensuring that this develops as one integrated market. I believe that this is vital to the success of the industrialisation process in this country.

To conclude my remarks, I would like to quote from the important 2011 paper by Dr Obi Iwuagwu of the University of Lagos entitled: “The Cluster Concept: Will Nigeria’s New Industrial Development Strategy Jumpstart the Country’s Industrial Takeoff?”

“The quest for rapid industrialisation in order to facilitate economic development has remained the focal point of successive administrations in Nigeria since independence. This is demonstrated by the multiplicity of industrial policies and strategies, initiated and implemented by the country over the period…(However) the industrial sector currently contributes a paltry 4% to national GDP…It was not as if the policies were not suitable for the country but that in most cases they were either not properly implemented or the implementation processes were truncated midway. Hence, it identifies policy inconsistency and the lack of political will to implement as the real challenges of Nigeria’s industrial development…The rapid growth of the Asian Tigers in particular is easily traceable to the pursuit of sound industrial policies initiated by their governments but implemented with the patriotic support of the private sector…Industry is yet to receive the attention it requires from Nigeria’s governments given its critical role as a growth driver. In other words, aside (from) enunciating new economic policies, Nigeria must be willing to tread the path of industrial development, which will enable it to add value to its primary resources (especially agriculture and minerals).”

I believe that having drawn the necessary from the account represented by such focused studies as represented by Dr Iwuagwu’s paper, Nigeria and indeed the rest of Africa, will take the required action to ensure that five years from today we no longer lament (i) the absence of sound industrial policies, (ii) improper or truncated implementation of these policies, and (iii) the absence of political will to achieve the industrialisation of our countries and Continent.

Thus should all of us, together as Africans, bind ourselves to the commitment H.E. President Buhari made when he spoke at Chatham House in London in February this year, that: “We must reform our political economy to unleash the pent-up ingenuity and productivity of the Nigerian (and African) people, thus freeing them from the curse of poverty. We will run a private sector-led economy but maintain an active role for government through strong regulatory oversight and deliberate interventions and incentives to diversify the base of (the) economy, strengthen the productive sectors, and improve the productive capacities of our peoples and create jobs for our teeming youths."

By Thabo Mbeki,

Former President of South Africa