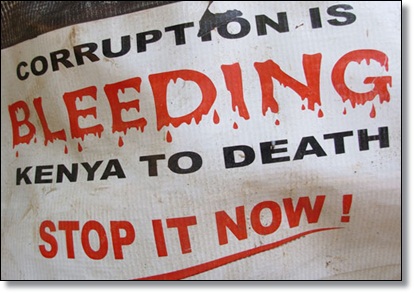

War on Corruption: Role of Individuals and Institutions

|

However, it is commendable that no politician, from the Jubilee/Cord has ever dared to remonstrate in praise of corruption. Yet, despite this clear unanimity of views against it, graft can be seen galloping with increased pace across all the facets of our social fabric.

As it careens out of our control, we only manage complaining about it in benumbed helplessness. The routine stance of government officials is that already, there are measures in place to strengthen the framework for apprehending and prosecuting offenders of corruption. Assurance is made of zero tolerance for office abuse.

The critics of government, and most probably the Opposition, accuse the Jubilee government of not wholeheartedly using the law. They berate it for doing so selectively. They ask for greater arrests and prosecution of suspected offenders. The focus of fighting graft is thus shifted and confined only to the stricter application of the elements of the law. This deflects the critical debate from its other essential ingredients.

By itself, law is not an exhaustive safeguard of moral excellence, justice or fairness. Our laws too have been found to be unjust and corrupt. Hence, every economic system brings into play the standards by which the members of a society make their living. These tenets delineate what is moral and lawful from the immoral, illegal or the corrupt. For instance, the slave conditions under which Africans were shipped from their homeland to the Americas deprived them of rights that even the goats of their forefathers ordinarily retained. A village goat heedlessly snaps a leaf from the garden for its unauthorized meal without much consequence to itself, but a Negro slave was liable for hanging for munching half a carrot from the heap he was harvesting for the master. Before the advent of colonial rule, the peasants in our different communities shared in the weal and woes of their lot. It was unethical and corrupt for anyone amongst them to have a meal alone in seclusion or to guzzle a gourd of local brew without inviting the neighbours. But today, in the closeted gardens of fenced mansions, it constitutes an offence to go to these homes uninvited or to be a scrambler for lunch!

The inaugurating Constitution 2010, Kenyans dreamed of establishing a sensitive state that would express the feelings of our people for securing dignity and their wherewithal from the alienating economic and political system. This entailed putting an end to the autocratic culture of the colonial and neo-colonial state, by superseding it with democratic relations with the population and the display of humility in service of them.

Much of the spectrum for making judgment on political conduct falls outside the narrow ambit of the law. The statement that combating corruption must lie mainly in prosecution disregards the inadequacy of the law. There is a simple legal notion that the one who offers a bribe is equally culpable like the one who solicits for it. In real life, the people who waddle in money or the position of office are invariably more powerful and entrenched than the supplicants who have to prostrate before them for favours. Moreover, to claim that both have equal liability is itself corruption.

Currently, many of the people accused of corruption or abuse of office have structured supervisors above them. Yet, we find these supervisors largely unaffected by their obvious lapses in ensuring discipline and order in their fields of oversight. Hence, the fight against graft can gain strength and credibility only if it combines legal sanctions with many other organized efforts to improve systems and methods. The health of humans does not depend solely on the administration of medicine. It relies on many other factors such as nutrition, work, exercise and general hygiene. Likewise, human society cannot be free from the graft menace without building political hygiene in our relations. Kenyans must go beyond mere lamentations.

By Vincent Oloo Mungao

The author is the Chairman Technocratic Age Group of Companies. The views are his own.